Study findings prove helpful in furthering eye disease research

Dr. Jeffrey Kiel, professor in the Ophthalmology Department at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, led a recent study with co-investigator Dr. Anthony Comuzzie, Scientist in the Department of Genetics at Texas Biomed, to determine whether baboons develop retinal lesions similar to those found in human diabetic retinopathy. The study aimed to show whether baboons could serve as an appropriate model to examine diabetic retinopathy.

The study was conducted as part of the Southwest National Primate Research Center Pilot Research Program. The program provides support to investigators for highly focused, short-term studies using non-human primates that enhance the value, practicality and appeal of nonhuman primates in biomedical research.

“The field has been looking for an animal model that more closely replicates what diabetes does to the human eye,” Kiel said. “We don’t have an animal model where we can study the natural progression of the disease and therapies for this devastating disease.”

Dr. Comuzzie has been performing diabetes research in the baboon colony for years, concentrating on genetic studies. Recently, his work has focused more specifically on diabetic complications, such as diabetic retinopathy.

“My group and I have clearly demonstrated that the baboon is susceptible to the development of diabetes and appears to display the same pattern of clinical progression,” Comuzzie explained. “These observations have led us to speculate that the baboon may also develop the same types of complications generally seen in humans. We had already identified animals with evidence of diabetic kidney disease, so I was very pleased to have the opportunity to work with Dr. Kiel to try and extend this work to include diabetic related eye disease, and I am very excited by the findings of this new collaboration.”

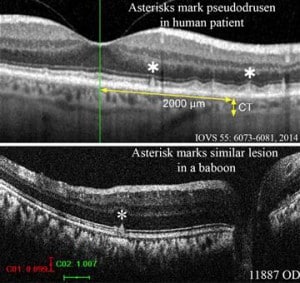

“I was hoping to find five out of 20 baboons with diabetic retinopathy, and we saw 19 out of 20,” Dr. Kiel said. “Even more surprising was a lot of animals had retinal pathology that looked like age-related macular degeneration.”

Kiel explained that in order to start seeing macular degeneration (AMD), you have to have an animal like the baboon that has a macula and that lives long enough. Rodents have been a primary model for studying eye diseases but they don’t have a macula and they simply don’t live long enough to see naturally occurring macular degeneration. Baboons at SNPRC can live about 25-30 years, which is long enough to see these effects.

“This has a lot of potential going forward,” Kiel said. “Age-related macular degeneration is one of those things that if you live long enough, you’re going to get it. We would love to slow or stop the progression. Within the baboon colony, if we were try a therapy, we also now have the technology in ophthalmology to measure it and see if it works before moving into human populations.”

Dr. Comuzzie said, “The documentation of what appears to be diabetes related eye disease in the baboon not only represents a great opportunity for both of our labs to expand our work in this area but potentially represents a significant advancement for all investigators interested in the use of such a well characterized animal model for use in translational research into the treatment of this significant condition.”

Dr. Kiel explained the usefulness of the baboon model when discussing the particular progression of macular degeneration from the dry form to the wet form. Nearly 10 percent of AMD cases involve a more damaging wet form of AMD where people with dry form AMD suddenly begin to grow immature, leaky blood vessels. These leaky blood vessels can cause scar formation leading to retinal detachment, which can cascade into blindness.

“What we don’t know is what causes transition from dry AMD to wet AMD, and you need an animal model with a macula that is similar to a human macula to test factors that impact this transition,” Kiel said. “That’s the strength of an animal model. We can study the natural course of the disease.”

Dr. Kiel has submitted several additional grants to various funding organizations that will allow for follow-up testing, including testing two new drugs that look promising against diabetic retinopathy in rodent models but need to show effectiveness in a nonhuman primate model.

*Image courtesy of Dr. Kiel